HAKATA, FUKUOKA

Hakata-ori

Silk textiles by way of China

Hakata-ori first originated in 1241 during the Kamakura period when Yazaemon Mitsuta, a merchant from Hakata made the journey to Song Dynasty China with a Zen Buddhist priest Enni (Shoichi Kokushi). On his return he was armed with a bounty of Chinese weaving techniques including “karaori.” This was the start of the Hakata-ori story.

At the time, Hakata was part of the ancient province of Tsukushi, and was a lively port town where trade thrived. An entry-point from continental Asia, a bounty of cultural imports passed through the town. Alongside exotic textiles, Yazaemon also introduced people to different artefacts and artisanal techniques – crimson glazing, the application of gold leaf, somen noodles and the production of musk pellets. Of all these things that Yazaemon introduced to the people of Hakata, only the textiles and woven goods were incorporated into the region’s culture and tradition. Its weavers have passed down these traditional techniques to the present day, while continually adding their own original touches.

Originally, the Hakata-ori was a thin, narrow band. It was said that these bands were used as obi’s on male kimonos. But gradually, over time, the obi width grew thicker and by the mid-Edo period it resembled the obi-thickness we see used in present day. Because Hakata-ori was always made using silk threads, it would have always been regarded as a highly precious and valuable item.

Creating the Hakata-ori Patterns

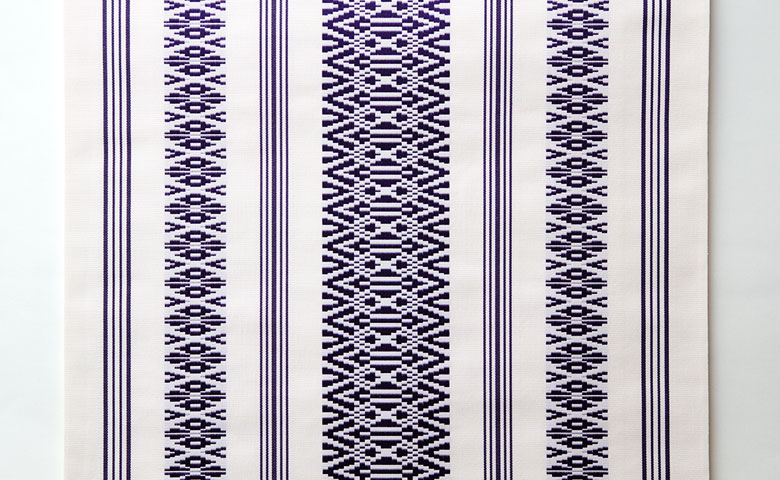

The Hakata-ori textiles are unusually thick, compared with other regions in Japan. This is due to Hakata-ori’s unique weaving process. Six to fifteen thousand threads are used for the warp, thick threads are used for the weft and are tightly woven into the warp to create a thick and resilient fabric cloth.

There is also a unique quality to the patterns of Hakata-ori fabrics. For example, whereas Kyoto’s Nishijin-ori weaves patterns into the weft, Hakata-ori weaves the patterns into the warp of the fabric. Because of the nature of this weaving method, the weavers create more simple, striped, graded or kenjo-gara patterns. These patterns are created by using hole-punched sheets of thick cardboard called “mongami.” It is the patterns on these cards that input the pattern-weaving data into the looms.

The charm of Hataka-ori is the ease in which they can be tied. “Hakata-ori obi are easy to tie and never slacken in shape,” say regular customers. When the obi is tightened, the Hakata-ori silk makes a signature, pleasant rustling sound.

The Merchants of Hakata and Hakata-ori

There are many festivals in Hakata, the birth-place of Hakata-ori. The most prominent festival however is the “Hakata Gion Yamanasaka,” a festival said to have been initially established by Shoichi Kokushi.

When this celebratory season came round, historically, the festival-loving male merchants would put aside their business affairs for an entire month and invest all their energy into preparing for the festivals. While these merchants were absent, the wives would be in charge of the home and have to manage their husbands’ business affairs. When these merchants returned to their wives after the festival season was finished, it was a custom that they would present their wives with a new kimono and obi, by way of apology for their month-long absence. Single-mindedness, rough around the edges but with a gentle heart. These are said to be the qualities of the Hakata gentleman.

The precious Kenjo-gara

The “kenjo-gara” is a precious and unique design within the Hakata-ori offering. The pattern has been inspired by implements used in Buddhist rituals such as the dokko (a metal hammer), hanazara (ritual plate) and also stripes. This kenjo-gara pattern was originally proposed by the monk Shoichi Kokushi (Enni) who had travelled to Song-dynasty China with Yazaemon. The name kenjo-gara were taken from Nagamasa Kuroda, feudal lord of Chikuzen who ruled over Fukuoka. He chose to include these hakata-ori textiles to the Tokugawa Shogunate as one of the obligatory tribute gift offerings – kenjohin – which is why this particular hakata-ori pattern was then named kenjo-gara.

During the Edo Period, people’s lives became easier and more prosperous and weaving techniques also became more advanced. Ordinary people could afford to buy woven textiles, but not the kenjo-gara which was strictly and exclusively reserved only for the Kuroda clan. Only twelve weaving workshops were officially sanctioned by the clan to make this pattern and for this reason, hakata-ori never rose to the same national prominence as other specialist regional textiles such as nishijin silk.

Hakata-ori: The changing of the times

At the beginning of the Meiji period, the sanctions on Hakata-ori and the kenjo-gara were lifted. Common people were allowed to wear these obi. Time passed and Japan moved through the ages, into the Taisho, then Showa period.

In post-war Japan, day to day survival became the sole priority, but as the country started to recover in the mid-50s, people had the means to purchase clothing again and the textile industry also recovered. From 1955-1965, Hakata-ori went through a golden age as the number of weavers rapidly increased. But when cars became commonplace in the mid-60s and 70s and people discovered that it was tricky to drive when wearing a kimono, they started to favour western clothing. Then there was a sartorial shift as people stopped wearing kimonos on a daily basis.

The position of men and women started to become more equal and as households where both the man and the woman went to work increased, so did their income. As a result, women lost the free-time they once had to put on a kimono and tie an obi and this marked a shift in Japanese attitudes to the kimono.

Customers nowadays demand a higher quality from their daily clothing and they also require that it expresses and matches their sense of individuality. In turn, clothing manufacturers have also shifted their mind-set and instead of reckless mass-production, some are now striving to make high-quality items. In this way, weavers are graduating from the standard and uniform designs of the past and moving into an era where the individuality of a textile weavers’ creations are flourishing. This is also an important turning point for Hakata-ori.

Presently, Hakata-ori textiles are worn throughout the country and prized for their quality, but the merchants of Hakata never rest on their laurels. Hakata merchants, who embrace novelty while cherishing tradition are investing in new efforts, attempting, with new designs and modern colours, to make Hakata-ori textiles appeal to a new generation of young people. As long as there are people who love kimonos, it is important to respond to that demand.

It is the mission of these artisans to continue the history of their predecessors.